TOKYO (AP) — South Korea’s President Yoon Suk Yeol faced parliamentary moves to impeach him after he sent heavily armed forces into Seoul’s streets with his baffling and sudden declaration of martial law that harkened to the country’s past dictatorships.

Opposition parties submitted the impeachment motion just hours after parliament unanimously voted to cancel Yoon’s declaration, forcing him to lift martial law about six hours after it began. Impeaching Yoon requires the support of two-thirds of the National Assembly and at least six of the nine Constitutional Court justices. The liberal opposition Democratic Party holds a majority in the 300-seat parliament and has called for Yoon’s resignation.

A vote on the impeachment motion could be held as early as Friday, Democratic Party lawmaker Kim Yong-min said.

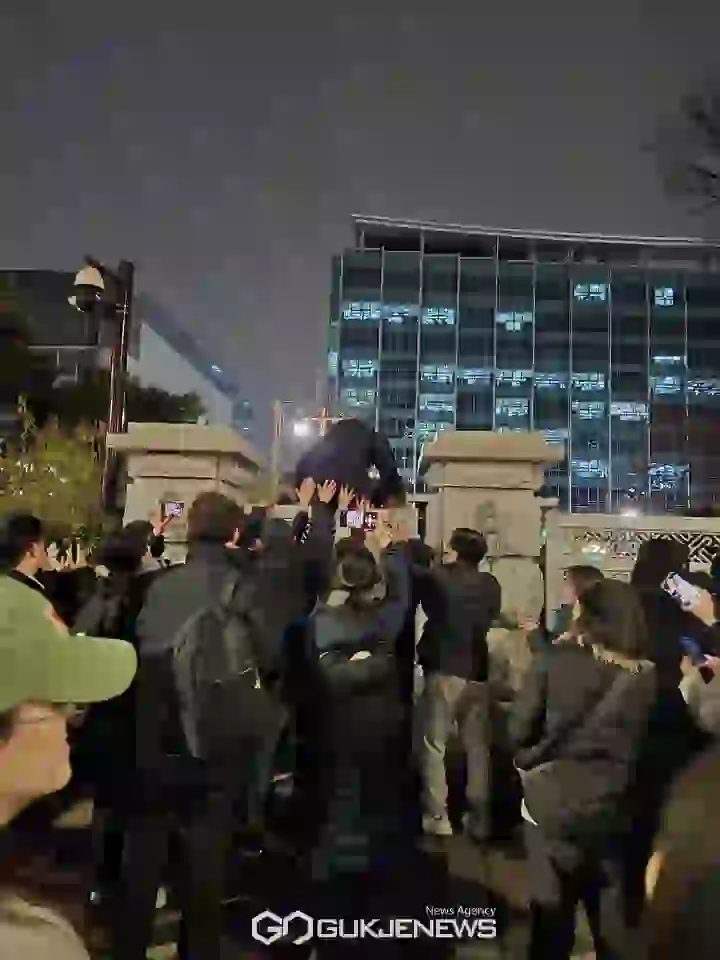

During the tense hours under martial law, heavily armed forces surrounded the parliament, backed by army helicopters and armored vehicles. Lawmakers climbed walls to get into the building and held off troops by activating fire extinguishers. Politician and former news anchor Ahn Gwi-ryeong tried to pull an assault rifle away from a soldier who had pointed it at her chest as she shouted: “Aren’t you ashamed of yourselves?”

The lawmakers who managed to reenter the building rejected Yoon’s martial law declaration 190-0, including 18 lawmakers from Yoon’s party, forcing Yoon to rescind it at a hastily assembled Cabinet meeting.

Here’s what to know about the situation in South Korea:

Yoon blamed an ‘anti-state’ plot but details are vague

Yoon ordered martial law without warning in a speech late Tuesday where he vowed to eliminate “anti-state” forces he said were plotting rebellion and accused the main opposition parties of supporting the country’s rival, North Korea.

Yoon gave no direct evidence when he raised the specter of North Korea as a destabilizing force. Yoon has long maintained that a hard line against the North is the only way to stop Pyongyang from following through on its nuclear threats against Seoul.

Until the late 1980s, South Korea had a series of strongmen who repeatedly invoked North Korea when struggling to control domestic dissidents and political opponents.

Yoon has struggled to get his agenda through an opposition-dominated parliament while facing corruption scandals involving him and his wife.

What is martial law?

Just this month, Yoon denied wrongdoing in an influence-peddling scandal involving him and his wife. The claims have battered his approval ratings and fueled attacks by his rivals.

The scandal centers on claims that Yoon and first lady Kim Keon Hee exerted inappropriate influence on the conservative ruling People Power Party to pick a certain candidate to run for a parliamentary by-election in 2022 at the request of Myung Tae-kyun, an election broker and founder of a polling agency who conducted free opinion surveys for Yoon before he became president.

Yoon has said he did nothing inappropriate.

Martial law has a dark history in South Korea

South Korea became a democracy only in the late 1980s, and military intervention in civilian affairs is still a touchy subject.

During the dictatorships that emerged as the country rebuilt from the 1950-53 Korean War, leaders occasionally proclaimed martial law that allowed them to station combat soldiers, tanks and armored vehicles on streets or in public places to prevent anti-government demonstrations.

Such scenes are unimaginable for many today.

Dictator Park Chung-hee, who ruled South Korea for nearly 20 years before he was assassinated by his spy chief in 1979, led several thousand troops into Seoul in the early hours of May 16, 1961, in the country’s first coup. He proclaimed martial law several times to stop protests and jail critics.

Less than two months after Park’s death, Maj. Gen. Chun Doo-hwan led tanks and troops into Seoul in December 1979 in the country’s second coup. The next year, he orchestrated a brutal military crackdown on a pro-democracy uprising in the southern city of Gwangju, killing at least 200 people.

In the summer of 1987, massive street protests forced Chun’s government to accept direct presidential elections. His army buddy Roh Tae-woo, who had joined Chun’s 1979 coup, won the election held later in 1987 thanks largely to divided votes among liberal opposition candidates.